Knowing Through Compassion

An Introduction to Wagner's Parsifal

(Note: This post is too long for an email, so it may be “clipped” by Gmail or whatever. There is not much philosophical analysis in the following essay, but it does provide a general map and some themes for a listener to begin to appreciate Parsifal. If reading this makes you want to try to watch or listen to Parsifal for yourself, it has succeeded. It was, however, written in a single afternoon, but that’s the kind of thing Substack is for, right?)

Recommended Recordings

First, a note about recordings of Parsifal. There are two well-nigh perfect audio recordings which I whole-heartedly recommend:

Knappertsbusch, Bayreuth 1962

Amfortas: George London

Titurel: Martti Talvela

Gurnemanz: Hans Hotter

Parsifal: Jess Thomas

Klingsor: Gustav Neidlinger

Kundry: Irene Dalis

Kubelik, Symphonieorchester des bayerischen Rundfunks

Amfortas: Bernd Weikl

Gurnemanz: Kurt Moll

Titurel: Matti Salminen

Parsifal: James King

Klingsor: Franz Mazura

Kundry: Yvonne Minton

The Knappertsbusch is a live recording, and a bit more “mystical”, slower in parts, shimmering. Hans Hotter is a perfect Gurnemanz, despite his age (this is after his bout of vocal trouble in 1958 from which he never fully recovered). This is good, because Gurnemanz sings more than anyone else in the entire work, as much or maybe even more than Parsifal and Kundry combined. The Kubelik, on the other hand, is a studio recording, a bit more polished, with better sound quality. Kurt Moll is once again a fantastic Gurnemanz, purring through the deep melodies with ease, and less shakily than Hotter. I focus on Gurnemanz also because, if the Gurnemanz is bad or even just somewhat boring, the whole opera falls apart. There are many good Parsifals, but few good Gurnemanzes.

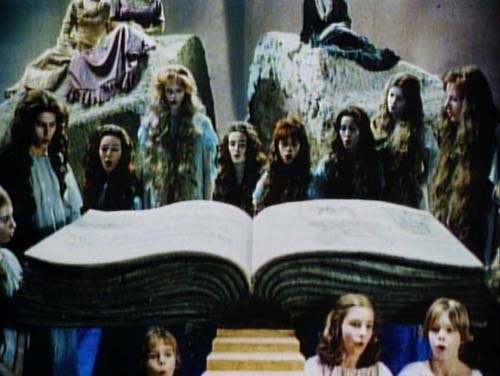

As for video recordings, I can recommend the Hans-Jürgen Syberberg film (with almost psychedelic sets and very strange camerawork) and the classic Met staging (the one with Siegfried Jerusalem and Waltraud Meier, which once again has the inimitable Kurt Moll in the role of Gurnemanz).

The Prelude

The music of Parsifal is like a haint which only crosses you when you aren’t looking. My grandfather always told me, in wonderstruck and reverent tones, that Parsifal would get stuck in your head such that you’d be humming it all night in your dreams, but, upon waking, you would be unable to remember the melodies with any definiteness. Only their aura would remain, they themselves having evaporated before your very eyes. And they would return only in the odd moment when, your mind wandering far, they would slide themselves into the back of your head and enchant you once again, and the longer you refrained from looking, the longer would last the spell.

The prelude to Parsifal begins quietly in the strings. It rises, displaying the fundamental motif. The strings soon step aside and allow the brass to sound the “faith motif”. The entire prelude remains by turns tranquil and epic, but never becomes tempestuous. Notably, it sticks rather close to its few motifs; it is nothing like an overture wherein the whole development is present in simplified form. Rather, its function is to draw us into the realm where that development can later occur. This is not to say that the prelude does not contain the whole drama, but it does so only in seed form, and purified of the many conflicts that will be encountered.

The drama in Parsifal, indeed, is otherworldly. The villain is vanquished by the end of Act II, and he barely causes any actual trouble. There is no plot twist in Act III where he comes back to wreak havoc. The drama functions on a different level than individual characters involved in conflict with one another. The plot exists on a far more symbolic level, if indeed it can really be called a “plot”. It is not a tale of outward victory, but of inward triumph. The most important elements are not to be found in the actions of the singers on stage, but in the music, which is to say, in their and our souls.

Indeed, not many things possess this power of enchantment, dreaminess, mysticism. Of Wagner’s works, Parsifal is the only one which really delves into that territory. Of course moments of Lohengrin suggest the Grail Kingdom, but they never display it, never come close enough to the shrine. Certain scenes of Tristan und Isolde, likewise, grope in the dimness towards a kind of death-mysticism, the unity of mutual extinguishment. But this still is too willful to be properly mystical. Tristan’s overwhelming passion, which makes his voice to waver and his limbs to quake, ensures he will never find the hidden pathway to Monsalvat. That great edifice of Will, Der Ring des Nibelungen, likewise cannot force an approach to the domain of Parsifal, though something of the veil itself may be glimpsed in the lamentations of Erde, the earth goddess. Even there, her chthonic message is one of foreclosure; the Fates weave, and all the meddlings of mortals and gods, even the great columns of force ejected by Wotan, cannot suffice to have any effect. Eventually the spear of Law is shattered by Nothung (Need), and from then on the gods resign themselves to their passing.

But there is another spear, a “wunden-wundervoller heiliger Speer” (wounding-wonderful holy spear), not a weapon of Law, nor yet of Chaos, but only of self-referential might.

Act I

In a misty and already-legendary era, just past but simultaneously at the Beginning, a pious hero, Titurel, experienced the ministrations of angels. Descending upon him, they gave unto him the Cup, from which the Savior drank at the Last Supper, and into which His blood was spilled. The Grail motif itself is based on the “Dresden Amen”, which Wagner would have heard echoing from a nearby church when he was but a child.

So too the angels passed down to him the Lance which drew the very blood that flowed into the Cup. Titurel built a shrine in a sacred wood, a place only accessible to the pure of heart, and soon gathered a company of knights to himself. The unveiling of the Grail for Communion is the centerpiece of their brotherhood.

Not all of his knights could live up to the chaste ideal, however. One of them, Klingsor, could not conquer his carnal inconstancy. Making a mad attempt to do so by force of arms, he castrated himself. For this crime, he was exiled from the Grail Kingdom.

What can only be conquered by struggle and suffering, he sought to do away with by violence. What can only be subdued by one’s own submission, by self-abnegation and humility, he sought to make an object of his own raging will. Klingsor is therefore something like a pre-Parsifal Wagnerian hero, a creature of force and not of resignation. The theme of redemption through love is also present, though here we see some of its fruits, and it will be decisively rejected by Parsifal himself at the end of Act II.

Klingsor, upon his expulsion from the company of knights, became (of course) a black magician, undoubtedly aided in this by his castrated but still entirely too willful state. Setting himself up in a kind of Garden of Earthly Delights, he used magic to establish for himself a kingdom of lustful knights and, as their lovers, a harem of Flower Maidens. There, they seek to lure the Grail Knights into sin.

One such seduction was all too successful. Titurel, aging and lying in his own grave, passed the rulership of Monsalvat to his son, Amfortas. But Amfortas, like Klingsor, could not totally conquer his lusts. He was seduced by Kundry (on which more soon), and in that moment Klingsor captured the Lance, stabbing Amfortas in the side. The wound will not heal, and it causes the young king immense suffering. He longs only for death, though he must do his duty as master of the Grail, the unveiling of which serves to preserve him (and Titurel) in life. But such grace is immensely painful to Amfortas, and when he drinks of the Precious Blood his wound becomes a fountain, pulsating and spilling the divine gift back out onto the ground.

Nonetheless, Amfortas’ suffering is of a different type than Klingsor’s. Klingsor’s act was final; he attempted to cut off the Will to sin at its source. Amfortas suffers his own inconstancy, and despite his impurity, his reward is different. Even though he is bereft of hope, he is eventually healed through the intercession of Parsifal.

There is, however a prophecy. A voice from heaven wafts down and tells of the way to redemption:

durch Mitleid wissend,

der reine Tor,

harre sein',

den ich erkor.

That is:

Knowing through compassion,

the pure fool;

wait for him,

the appointed one.

The fool is one who is pure, or innocent. He is initially amoral, but comes to enlightenment through compassion. Of course this is Parsifal, and he first appears on stage after shooting a swan in the sacred wood, for the simple reason that he can, for the pure delight he takes in his own ability with bow and arrow: “I can hit anything that flies!” Knowing nothing of himself, nor having any consideration for the morality of his actions, but clearly not expressing malice or ill-intent, Parsifal initially appears to Gurnemanz as the one they have been seeking, the pure fool. After being told that his mother has died by Kundry, he attacks her in anger, only to be stopped by Gurnemanz. Surely, Parsifal is a fool. But is he the one?

To test this, Gurnemanz brings Parsifal into the Grail Kingdom. A sequence follows wherein the stage transforms before the audience’s very eyes. Here Wagner envisioned a mechanism that moved the stage backdrop behind the singers as they slowly walked. (Imagine a giant scroll with scenery painted on it, perhaps connected to a motor, which makes it appear that the singers are moving far more quickly than their feet could possibly take them as the scenery changes at a rapid rate.) As Parsifal comments:

Ich schreite kaum,

doch wähn' ich mich schon weit.

That is:

I scarcely tread,

yet seem already to have come far.

To which Gurnemanz responds:

Du siehst, mein Sohn,

zum Raum wird hier die Zeit.

That is:

You see, my son,

time here becomes space.

This transition brings with it the famous “Transfiguration Music” [Verwandlungsmusik]. It is one of the most beautiful pieces of music Wagner ever wrote. (Note: the linked video contains the Transfiguration Music from both Act I and Act III; the latter piece also includes Titurel’s funeral procession, on which more later.) The so-called “suffering motif” brings us into the reality of Monsalvat, with its wounded king and damaged faith.

The tonality here is hard to pin down, Wagner having learned much from his composition of Tristan. Unlike the music in the Grail Kingdom itself, which is more tranquil with its choirs and Mass-like atmosphere, the Transfiguration Music is unsettling, awe-inspiring, growing to great crescendos and changing keys in incredible ways. It weaves together a number of motifs, finally ending with the bells which call the knights to the supper.

Amfortas despairs of his inheritance as King, and only reluctantly fulfills his duty to the Grail and to the knights. What follows, Communion, has already been referenced. It is an incredible use of chorus, a truly transcendent atmosphere emerging as the Grail is presented. The mysterious swirling of the violins complements the epic but melancholy trumpet fanfares. Something is happening, but you won’t see it on stage.

Gurnemanz now asks Parsifal if he understands what he has seen. Of course he does not. He is shocked, and remains silent. For this, Gurnemanz declares him not the Savior but simply a fool, and casts him out.

Act II

Act II begins with Klingsor’s music (which was already established in seed form back in the Gurnemanz aria “Titurel, der fromme Held” above). Agitated violin runs meet with an evil swirling and swelling reminiscent of a transformed Grail scene. Several times, in fact, Klingsor almost sings the Dresden Amen or other pious themes only to have them collapse into catastrophe on the last note.

What follows the prelude is a truly evil scene. Klingsor, the castrated magician, awakens Kundry from her death-like slumber and commands her to go seduce Parsifal. Here we learn something of Kundry’s past.

Kundry is a strange character. In Act I, she was seen helping the knights, bringing balsam to Amfortas, delivering messages to crusaders in faraway lands, and so on. There, she was a wild woman, viewed with suspicion by the young knights as a pagan and sorceress. As it turns out, she has been cursed to reincarnate endlessly until she can be redeemed by the anointed one. Her great sin was mocking Christ on the Cross. Klingsor alleges that in past lives she has been many great and evil women, including Herodias. She is the “Rose of Hell”, a “primeval devil-woman”. And it was she who seduced Amfortas.

But she feels great remorse. She finds the task disgusting. The reason why becomes clear later in Act II: She can only be redeemed by the one whom she cannot seduce. She is the danger, and in seeking her redemption she destroys it and damns herself all the more. In her work as temptress, she secretly hopes she will not succeed, but in all her wanderings she has always succeeded. Is there not one chaste knight? Where is he that can conquer his own inconstancy? And after each triumph of lust, she wants to weep, but can only laugh.

Parsifal mounts the walls of Klingsor’s castle. The knights of the flesh are summoned, and easily dispatched by the fool. Knowing he cannot win by force of arms, Klingsor calls upon the Flower Maidens.

They fight over Parsifal and make their advances, and his innocence leads him to the brink of failure, but ultimately he is repulsed by them. The female chorus here is one of the best Wagner ever wrote (at the risk of saying that about almost everything to be heard in Parsifal…). The maidens sing over each other, mounting ecstasy washing over Parsifal. The maidens are at first angry that Parsifal has slain their bedfellows (Klingsor’s knights), but easily turn their amorous intentions on him. The music here is the exact opposite of the ponderous and slow mysticism of the Grail Kingdom. It is purposely frivolous, ornamented, relatively fast, and, in a sense, wholly empty. Once the “Komm, komm, holder Knabe” part begins, however, a luscious sensuality replaces the maidens’ frivolity and agitation. With long and sinuous vocal lines the maidens beckon Parsifal to come and “pluck” them. The singing becomes ornamented with trills and runs.

Kundry now appears, and what follows is the central conflict of the opera. As he decisively rejects the Flower Maidens, she calls out him, “Parsifal! Wait!” His name seems to put him in a trance. His mother, dreaming, gave him this name.

Kundry now attempts her seduction of Parsifal. She opposes her own approach to that of the Flower Maidens. Whereas they sought him in obvious, crude, and overtly sexual ways, Kundry will attempt to awaken his grief and so start to break him down by “comforting” him. To this end, she sings her most beautiful aria, “Ich sah das Kind an seiner Mutter Brust” (“I saw the child at his mother’s breast”). She awakens Parsifal’s feelings for his mother, Herzeleide, whom he had abandoned in seeking out adventure in the forest and playing at being a knight. Parsifal’s father, the knight Gamuret, died in a foreign land while on crusade (or something of the sort). Kundry sings of Herzeleide’s love for her child, of her desire to protect him from the same fate that befell Gamuret. She delighted in Parsifal’s growth into a young man, but when he left her, she died of heartbreak.

The aria is bizarre. Its structure is by no means clear upon listening. A crescendo and a great climax (3:26 or so in the video) seem to come and go. The melodies are slippery, and cannot easily be recalled before the mind. Anxiety runs through the entire piece, and sorrow. Without a clear tonal center, it collapses at the end into the sad conclusion, “…und Herzeleide starb” (“and Herzeleide died”).

The effect of Parsifal is immediate. He weeps, “What have I done? Where was I? Mother…” Kundry moves in on him, seeking to take him in his hour of grief. She embraces him, declaring that to know his mother’s love, he must experience a substitute love - sexual love here with Kundry. A last token of his mother’s love for him, the only way for him to understand any of this, who he is and where he came from: she kisses him. Taste the love your mother had for you, under the aspect of her love with Gamuret. Burning passion engulfs him, a terrible longing. Parsifal leaps up.

“Amfortas! Die Wunde!” (“Amfortas! The wound!”) He feels it, in his own side! The wound from the Spear, it sears his heart. He now knows the greatest suffering: “I saw the wound bleed, now it bleeds in me!”

But it is not the wound. It is desire, and loss of innocence. The suffering motif finds its full expression in this aria. In any ordinary analysis of desire, the object is pursued as what will quench the state of dis-ease. But Parsifal does the exact opposite: desire is pain, and instead of giving into this pain, he renounces the desire altogether. He cries out:

Erlöser! Heiland! Herr der Huld!

Wie büss ich Sünder meine Schuld?

That is:

Redeemer! Saviour! Lord of grace!

How can I, a sinner, purge my guilt?

The pain of longing has led him even more to understand and dwell in the suffering of his mother. While she was in such an agony as this, he ran off to accomplish the foolish deeds of a child. Kundry had hoped for the pain and suffering to open the way to longing and sexual desire, but Parsifal has transmuted it into knowledge. Enlightened by compassion for his mother, by Mitleid (“suffering with”), Parsifal confronts himself as a sinner. He does not move to extinguish his sin in the calling of the flesh.

A major change has occurred in Wagner’s conception of redemption. All his previous works revolved around redemption through love. In prior operas, a character, usually a man but not always, was damned for some reason or another, and could only receive salvation through the selfless love of a woman. Witness Tannhäuser and Der fliegende Holländer. Or else the woman failed in her loving, though the promise was the same, as in Lohengrin. Or else both man and woman collapsed in a love that extinguished them, as in Tristan. Or else love was both redemptive and utterly cataclysmic, as in the Ring. But here, as Kundry continues her attempts, Parsifal declares:

Auf Ewigkeit

wärst du verdammt mit mir

für eine Stunde

Vergessens meiner Sendung

in deines Arms Umfangen!

That is:

For evermore

would you be damned with me

if for one hour,

unmindful of my mission,

I yielded to your embrace!

Kundry becomes more agitated, and more crude, and she begins to sing music initially heard from the Flower Maidens. Becoming more artless by the minute, she ends up begging him to save her through the sexual embrace. Finally, Parsifal commands her from his sight, at which point Klingsor appears with the Spear and readies his attack. The Spear is hurled, but hangs suspended over Parsifal’s head. He reaches up and grasps it, makes the Sign of the Cross with it, and Klingsor’s entire realm falls into ruin.

Act III

The third and final act of Parsifal contains almost no conflict whatsoever. In outline, Parsifal has been wandering the world trying to find the entrance to the Grail Kingdom once again to return the Spear. On Good Friday, he comes upon Gurnemanz, now a forest hermit, and the latter recognizes him. Parsifal is declared King of the Grail Kingdom, and is baptized by Gurnemanz. Parsifal then baptizes Kundry. Gurnemanz tells Parsifal that Titurel, deprived of the light of the Grail, has died. His funeral is to be held that very day, and they enter the Grail Kingdom. Parsifal heals Amfortas, and the opera ends.

The central scene of Act III is undoubtedly the baptism and its musical followup, the famous “Karfreitagszauber” (“Good Friday Spell”). In the baptism scene, the Dresden Amen appears in all its glory, with huge and overwhelming crescendos. It is contrasted with soft woodwinds as Parsifal ponders his new station. The Karfreitagszauber proper begins just before Parsifal’s line “Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heut’ so schön”. A good Gurnemanz can make the listener weep at this point in the opera (and Kurt Moll is at his best in the linked video; unbelievable).

The theological backdrop to the Good Friday Spell is worth pondering, once one has just basked in its beauty (which indeed is primary). Parsifal declares that the meadow is surpassingly beautiful, that he has never seen such beauty before. Gurnemanz responds that this is the magic of Good Friday. Parsifal unexpectedly erupts in grief:

O wehe, des höchsten Schmerzentags!

Da sollte, wähn' ich, was da blüht,

was atmet, lebt und wiederlebt,

nur trauern, ach! Und weinen?

That is:

Alas for that day of utmost grief!

Now, I feel, should all that blooms,

that breathes, lives and lives anew

only mourn and weep!

Gurnemanz responds that this is not the whole picture. In fact, it is the suffering of this day that makes it so beautiful. The tears of repentant sinners, as they contemplate the Savior’s sacrifice, water the earth and make it all to bloom. All creation rejoices, for in Man they behold an image of God, and if God so suffered, then Man himself will not deign to tread upon the little flowers. As God suffered for and pitied Man, so Man will suffer and pity all of creation on this day.

Gurnemanz reaches a crescendo of utmost beauty:

Das dankt dann alle Kreatur,

was all' da blüht und bald erstirbt,

da die entsündigte Natur

heut ihren Unschuldstag erwirbt.

That is:

Thus all creation gives thanks,

all that here blooms and soon fades,

now that nature, absolved from sin,

today gains its day of innocence.

It is worth asking the question of the relationship of Good Friday to Easter Sunday, the latter of which may appear conspicuously absent in Parsifal. However, it is not totally absent, and there is a potential analogue in the healing of Amfortas.

The second Transfiguration Scene follows, and once again we are treated to a strange labyrinth of twisting tonal centers and shifting moods.

This time, however, the heroic entry into the Grail Kingdom (the brass fanfare) leads into Titurel’s funeral music, and eventually the clanging bells and dissonant chords drown out any sense of triumph. We are entering a Kingdom on the brink of ruin. Titurel’s death was brought about by Amfortas’ reluctance to preside over the Grail. The knights are angry with him, as he is angry with himself. However, he has promised to unveil the Grail at least one more time, at his father’s funeral rites.

Once inside the Grail Kingdom, we see that the situation is dire indeed. Amfortas appears and sings another aria, this one a remorseful self-castigation for the death of Titurel. It ends however, with a longing for death, and he refuses to preside over the Grail, since doing so will preserve him in life and in suffering:

Hier bin ich, - die offne Wunde hier!

Das mich vergiftet, hier fliesst mein Blut:

heraus die Waffen! Taucht eure Schwerte

tief - tief, bis ans Heft!

Auf! Ihr Helden:

tötet den Sünder mit seiner Qual,

von selbst dann leuchtet euch wohl der Gral!...

That is:

Here I am, here is the open wound!

Here flows my blood, that poisons me.

Draw your weapons! Plunge your swords

in deep - deep, up to the hilt!

Up, you heroes!

Slay the sinner with his agony,

then once more the Grail shall shine clear on you!

Perhaps the knights are about to do just this when Parsifal enters. Triumphantly, he declares:

Nur eine Waffe taugt:

die Wunde schliesst

der Speer nur, der sie schlug.

That is:

But one weapon serves:

only the Spear that smote you

can heal your wound.

Only the very same weapon that caused the wound can heal it. Only the very same, and none other. The weapon can harm as well as hurt, but in all his wanderings, Parsifal never used the weapon for war, and in preserving it as a kind of weapon of peace he suffered many injuries.

The same God that was slain on the Cross is to be one who rises. A kind of resurrection is implied, though the emphasis is not on Parsifal, but on the wounded one, the suffering human nature represented by Amfortas, prey to his own folly. And only the innocent pure one, only a fool, could effect the mimesis necessary to identify with suffering, could understand it in an instant as if struck by a bolt of lightning - and for the sake of his mother! Only this could recover the Spear and so heal the suffering king.

The music becomes transcendent once again at the end, with the voice from Heaven coming down, and the ever-swirling violins, and the strange tonality. The opera doesn’t end so much as it sublimates itself, getting ever more rarefied until it simply evaporates into the ether.

As Parsifal achieved enlightenment through compassion, which in turn was achieved through the grace hidden within suffering and the identification with the suffering of another, so we are invited to a childlike innocence in the face of what we cannot understand. It is not that lack of understanding is a goal, nor is it that suffering is its own end. Compassion is the route to enlightenment, and it is gained by a kind of selflessness. Many have commented on the Christian themes of Parsifal, and Nietzsche hated Wagner for it (well, actually he probably hated Wagner for personal reasons, but the “Christianity” of Parsifal was a convenient target). The odor of piety may have been too much for Nietzsche. Others have decried Parsifal as not Christian at all, but Buddhist. It is certainly Schopenhauerian, its central theme being renunciation of the Will.

When Wagner himself was asked if Parsifal was supposed to be Jesus, he replied that “Jesus wouldn’t be a tenor!” Prior to Parsifal taking its final shape, he had been writing an explicitly Buddhist opera, Die Sieger (“The Victors”). But in the end he found the Christian symbolism too powerful to set aside, and for his purposes it sufficed, if it did not in fact amplify the emotional force of the finished work.

For Wagner, at any rate, symbolism was the core of the message. Not one for doctrine, he was not so much religious as symbolically sensitive. Whether he knew fully what he was doing is another question. But, whether because of his own beliefs or despite them, he reached a peak in Parsifal that he had not reached before, and was never to reach again. It was his last opera, and the full flowering of the philosophy that had been in development his entire compositional career.

In closing, Schopenhauer was the greatest modern philosopher solely for the influence he had on Richard Wagner. And Nietzsche was the worst modern philosopher solely for the influence Wagner had on him. It is best to listen to the entire ~4.5 hours of Parsifal, and, far from judging it, let it permeate you as only the greatest works of art can. Parsifal is certainly the greatest musical achievement of all time, but if it is not given the proper time and thought, no amount of writing can serve to “convince” the listener of this indisputable fact.